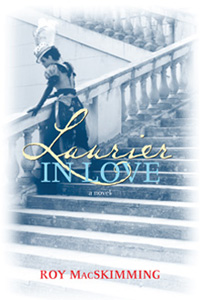

Laurier in Love

The publisher writes

Laurier in Love reveals Sir Wilfrid Laurier as Canadians have never known him: enmeshed in a passionate, enduring love triangle as he leads his country into a new century.

A gifted and wildly popular Prime Minister, Laurier is equally devoted to his quiet, faithful wife Zoë and his ambitious, charismatic lover Émilie Lavergne. The story is told through the eyes of these remarkably realized women – friends who are also rivals for Laurier’s heart. They must contend with the dark contradictions in his nature as he professes committment to both of them while uniting a divided nation.

Boldly imagined and brilliantly executed, Laurier in Love portrays Laurier the statesman, emerging onto the world stage at Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee; Laurier the silver-tongued orator, charming Americans in Chicago; Laurier the conciliator, bridging conflicts between English and French as Canada fights a distant imperial war in South Africa. Above all, we feel the joy and pain of two women who tie their destinies to the same man – until in the end he must act to resolve the impasse.

This is a novel both epic and intimate in scale. The cast of characters includes the aging Queen, the doomed President McKinley, a young Winston Churchill, an even younger Mackenzie King. Laurier in Love authentically and entertainingly recreates the man, the era, and the fascinating personal life Laurier led behind the scenes.

Main Characters

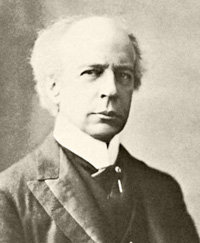

Sir Wilfrid Laurier

Elegant and charming, charismatic and eloquent, Sir Wilfrid Laurier was a leader of extraordinary gifts, achievements and contradictions. Becoming Prime Minister of Canada in 1896, he advanced the work begun by Sir John A. Macdonald of creating a vast new nation stretching across the northern half of North America.

Elegant and charming, charismatic and eloquent, Sir Wilfrid Laurier was a leader of extraordinary gifts, achievements and contradictions. Becoming Prime Minister of Canada in 1896, he advanced the work begun by Sir John A. Macdonald of creating a vast new nation stretching across the northern half of North America.

Laurier was the first French-Canadian Prime Minister, elected in an era when deep cultural and religious differences split the country. He worked tirelessly to keep the nation united while gradually freeing it from British imperial control. Many in English Canada opposed him, yet Laurier was immensely popular and held power for 15 years before being toppled in the 1911 election.

Laurier’s path to power was far from easy. Before winning a landslide majority, he spent nine difficult years as Leader of the Opposition. At first he rejected the Liberal Party leadership when it was offered, doubting that English Canada was ready to accept a French Roman Catholic as Prime Minister. But once in government, Laurier relished power and used it masterfully to pursue his goals.

Laurier’s path to power was far from easy. Before winning a landslide majority, he spent nine difficult years as Leader of the Opposition. At first he rejected the Liberal Party leadership when it was offered, doubting that English Canada was ready to accept a French Roman Catholic as Prime Minister. But once in government, Laurier relished power and used it masterfully to pursue his goals.

This is the man we meet in Laurier in Love: a newly elected leader swept into office by a people eager for change. Laurier would benefit politically from the country’s unprecedented prosperity and growth as settlers poured into the west. He would reluctantly lead the nation into its first foreign military adventure – the Boer War in South Africa – a conflict that resonates with today’s struggle in Afghanistan. And in his private life, he still had thorny issues to resolve, with deep roots in his complex emotional nature. Those issues are at the heart of the novel.

Zoë Laurier

Née Lafontaine, Zöe grew up poor in Montreal, the daughter of a piano-teacher mother and ne’er-do-well absentee father. As a young woman Zöe gave piano lessons to make ends meet. She was petite, slim, demure and retiring, but practical. She parted her dark hair severely in the middle, but her large eyes, delicately sculpted mouth and thoughtful, sensitive nature attracted Laurier when they were both boarders at the Montreal home of Dr. Gauthier and his family.

Née Lafontaine, Zöe grew up poor in Montreal, the daughter of a piano-teacher mother and ne’er-do-well absentee father. As a young woman Zöe gave piano lessons to make ends meet. She was petite, slim, demure and retiring, but practical. She parted her dark hair severely in the middle, but her large eyes, delicately sculpted mouth and thoughtful, sensitive nature attracted Laurier when they were both boarders at the Montreal home of Dr. Gauthier and his family.

As described in Laurier in Love, the Lauriers’ courtship was highly unusual. Laurier believed that, like his mother who had died when he was seven, he had contracted a fatal case of tuberculosis. He felt this meant he should never marry, and it was only a surprise intervention by Dr. Gauthier that convinced him otherwise.

After their wedding in 1868, the young couple lived in Arthabaska, Quebec, where Wilfrid practised law. As his practice flourished, they commissioned a distinguished local architect, Louis Caron, to build them an Italianate red-brick, two-storey home on a beautifully treed lot. By that time Laurier was the local Member of Parliament, eventually becoming a minister in the government of Alexander Mackenzie.

After their wedding in 1868, the young couple lived in Arthabaska, Quebec, where Wilfrid practised law. As his practice flourished, they commissioned a distinguished local architect, Louis Caron, to build them an Italianate red-brick, two-storey home on a beautifully treed lot. By that time Laurier was the local Member of Parliament, eventually becoming a minister in the government of Alexander Mackenzie.

For the Lauriers, life in Arthabaska (now a suburb of Victoriaville) was good. Although they had no children, their home life was filled with music and books, lively friends and political colleagues, young nieces and nephews. In the last year of his life, Laurier would write: “We were young then, and youth paints only en couleur de rose. Those days of Arthabaska! How gladly would I return to them.”

Meanwhile a new presence had arrived, one who would colour their existence till the end.

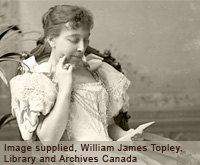

Émilie Lavergne

Born Émilie Barthe, she arrived in Arthabaska in 1876 after sojourns in Paris and London. Her father was a writer and, like Laurier, a politician of the Rouge persuasion. Émilie was charming, vivacious, cosmopolitan and well-read. Although hardly beautiful, she dressed in the latest Parisian fashions and possessed the self-confidence and social gifts that would make her a celebrated hostess.

Born Émilie Barthe, she arrived in Arthabaska in 1876 after sojourns in Paris and London. Her father was a writer and, like Laurier, a politician of the Rouge persuasion. Émilie was charming, vivacious, cosmopolitan and well-read. Although hardly beautiful, she dressed in the latest Parisian fashions and possessed the self-confidence and social gifts that would make her a celebrated hostess.

Émilie’s arrival created a sensation in provincial Arthabaska society. But as Zöe observes in Laurier in Love, she herself was the only wife in their circle who had anything to fear from Émilie, who had eyes for Laurier alone. Since he was already married, Émilie took the next best thing by marrying his law partner, Joseph Lavergne – a staid, conventional man who seemed slightly dazed by his good fortune in acquiring such a remarkable wife.

It wasn’t long before Laurier and Émilie created their own little book club à deux. They were both voracious readers of fiction, biography and poetry, and their mutual love of literature drew them together while giving them a plausible reason to spend so much time in each other’s company – with Zöe and Joseph’s apparent consent.

It wasn’t long before Laurier and Émilie created their own little book club à deux. They were both voracious readers of fiction, biography and poetry, and their mutual love of literature drew them together while giving them a plausible reason to spend so much time in each other’s company – with Zöe and Joseph’s apparent consent.

From remarks made to others, it’s clear Émilie saw herself not only as Laurier’s soulmate, but his mentor in worldly matters. She considered herself, not Zöe, as the most suitable helpmate to assist Laurier in achieving the highest office in the land. What else she wanted, and what she received, are mainsprings of the plot of Laurier in Love.

Gabrielle and Armand Lavergne

The Lavergnes had two extremely bright, spirited, attractive children, a girl and a boy, Gabrielle and Armand.

The Lavergnes had two extremely bright, spirited, attractive children, a girl and a boy, Gabrielle and Armand.

Laurier doted on them as much as their parents did. He paid for Gabrielle’s education at a Quebec City convent, and in his voluminous correspondence with Émilie he spent an inordinate amount of time dwelling on both children, asking after their welfare and prospects, dispensing advice about their upbringing. He was especially concerned that Armand acquire a mastery of English as well as French, so that he could play a leading role in society.

Was Laurier’s interest in the Lavergne children akin to that of an honourary uncle? Or was it something deeper and more intimate? Compare the photographs, read Laurier in Love, and decide for yourself...

The Lauriers’ Homes

Wilfrid and Zöe continued to own their home in Arthbaska until their deaths in 1919 and 1921, respectively. But after Laurier became Prime Minister, they moved permanently to Ottawa, using the Arthabaska house mainly as a holiday retreat – as in the scene in Laurier in Love when the Governor General and his wife, Lord and Lady Aberdeen, come to visit. Today the house is known as the Musée Laurier, a historic site open to the public.

Wilfrid and Zöe continued to own their home in Arthbaska until their deaths in 1919 and 1921, respectively. But after Laurier became Prime Minister, they moved permanently to Ottawa, using the Arthabaska house mainly as a holiday retreat – as in the scene in Laurier in Love when the Governor General and his wife, Lord and Lady Aberdeen, come to visit. Today the house is known as the Musée Laurier, a historic site open to the public.

From 1897 on, the Lauriers’ principal residence was 335 Theodore Street (now Laurier Avenue East) in Ottawa. Built of yellow brick in the Second Empire style, the house was acquired for the Lauriers by the Liberal Party. In turn, the Lauriers bequeathed it to the next party leader,  Mackenzie King. Thus the home was occupied for over half a century by two Prime Ministers. Known today as Laurier House, the home is a national historic site administered by Parks Canada, offering extraordinary glimpses into the private lives of Laurier and King.

Mackenzie King. Thus the home was occupied for over half a century by two Prime Ministers. Known today as Laurier House, the home is a national historic site administered by Parks Canada, offering extraordinary glimpses into the private lives of Laurier and King.

Love and Sex in the Capital

Of all Canada’s national leaders, Wilfrid Laurier led the most fascinating love life – at least until Pierre Elliott Trudeau came along. Indeed, many have remarked on the physical resemblance between the two romantically handsome Prime Ministers from Quebec.

In recent years Canadians have grown accustomed to thinking of their political leaders as lacking charisma and sex appeal. But it wasn’t always so. Consider a few examples from earlier in history...

Although homely and hardly glamorous, Sir John A. Macdonald, the subject of Roy’s novel Macdonald, radiated a natural warmth, humour and humanity that attracted people of both sexes. Sir John’s personal qualities were a large part of his political appeal, especially in a pre-television era when voters flocked to political meetings and picnics to meet their politicians personally.

John A.’s first marriage – to his Scottish cousin Isabella Clark – was happy for the first year or so, then increasingly difficult as Isabella became a chronic invalid. Her poor health was complicated by her addiction to the laudanum (opium) prescribed by her doctors for her pain and low moods, which doctors today might diagnose as depression. Isabella gave birth to two sons: the first, named after his father, died in infancy, but the second, Hugh John, became a lawyer like his father, an MP and Premier of Manitoba. Isabella died when Hugh John was seven.

John A. spent the next 10 years as a bachelor. As his political star climbed, he had little time to raise Hugh John, who was cared for by Macdonald’s sister and her husband in Kingston. But John A. didn’t lack for female admirers. One, Elizabeth Hall, the widow of an old friend of his, wrote him letters signed “love from loving Lizzie.” Another was Eliza Grimason, who owned a popular tavern in Kingston and often entertained Macdonald and his cronies. Eventually he began courting a much younger woman – the intelligent, well-read Agnes Bernard, sister of his personal secretary. But Agnes broke off the relationship by moving back to England.

As so often in his life, John A. refused to be discouraged. When in London negotiating the British North America Act, he met Agnes again and soon proposed marriage. Their wedding took place in February 1867, after which they returned to Ottawa for the birth of the new nation. The Macdonalds’ union was strong. Agnes received credit for curbing her husband’s drinking and providing him with a happy home life. Their only child, Mary, was born hydrocephalic, and they showered her with love and attention. In the end Mary outlived them both.

After Macdonald’s death, he was succeeded by four Conservative PMs in rapid succession, until Laurier’s accession to power. Two of these had notable love lives.

Sir John Thompson enjoyed a robust and evidently sensual marriage with his wife, Annie Affleck. John and Annie’s courtship was compromised by the fact that he was Protestant and she Catholic, but their mutual passion overcame this obstacle, a major one at the time. They wrote uninhibited, explicit love letters in shorthand to ensure her parents couldn’t decipher them. They addressed each other as “baby” and “pet” and wrote playfully about cuddling, kissing, even spanking.

After their wedding, Thompson converted to Catholicism to complete their union. Annie would bear him nine children, only five of whom would live to adulthood. Thompson was Macdonald’s Justice Minister, considered the most able man in cabinet, and became Canada’s first Catholic Prime Minister. He died in office at 51 from a stroke during dinner with Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, leaving his family in poverty.

Sir Charles Tupper was justifiably known back home in Nova Scotia as “the Ram of Cumberland County.” A doctor by profession, Tupper became Conservative Prime Minister in 1896, just in time to be defeated by Laurier. But long before that happened, Tupper had built a formidable reputation as Premier of Nova Scotia, Macdonald’s Minister of Railways and Canals, Canada’s High Commissioner to Great Britain, and an irrepressible ladies’ man. Tupper was a Father of Confederation and apparently much else.

Tupper was notorious not only for flirting with women – one journalist described him as “popular with the ladies in private conversation” – but pursuing them hotly and often successfully. On a trip to Washington, Sir John Thompson did his best to foil Tupper’s attempts to seduce an innocent young woman. In addition to his own children with his long-suffering wife, Frances, Sir Charles was accused in a lawsuit of impregnating a secretary and arranging an abortion for her. As a physician, he had access to both women and medical remedies. At the end of his days, Tupper was haunted by recurring dreams of his late wife.

Mackenzie King never married. Yet, as documented in his voluminous diaries, King lived a vivid emotional life marked by several important relationships. The best-known was with his mother, Isabel King, with whom he had an unusually – one is tempted to say “unnaturally” – close connection. As a graduate student, King was about to propose marriage to a girlfriend but changed his mind because the idea upset his mother too much.

Laurier in Love portrays the closest friendship of King’s life: a deep meeting of minds between him and his roommate, Bert Harper. After Harper’s tragic death trying to save a young woman from drowning in the Ottawa River, King had two lengthy dalliances with married women, both with the cooperation of their husbands. But his ultimate loyalty was to Isabel, whose eerily illuminated portrait hung like a shrine in his study long after her death. King repeatedly communicated with his mother’s spirit – and with Laurier’s too – through a medium.

John Diefenbaker, who remarried after his first wife died, apparently lived a connubially blameless life. But the same couldn’t be said about some of his cabinet ministers, including Associate Minister of National Defence Pierre Sévigny, who slept with a German-born prostitute in Ottawa named Gerda Munsinger. Since Munsinger also had Soviet clients, she was considered a security risk, and when the affair became public in 1966, Canada had its first political sex scandal. No security breach was ever proved, but reputations were ruined.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s relationships with celebrated women are legendary and well-documented. None ever came close to being a scandal, and it’s a mark of society’s growing hedonism during Trudeau’s time in politics – he first became Prime Minister in 1968 – that more Canadians admired him than disapproved. Trudeau’s frequent companions included television personality Charlotte Gobeil, singer Barbra Streisand, actor Margot Kidder and musician Liona Boyd.

But Trudeau’s most famous and poignant relationship was with his first and only wife, Margaret Sinclair, whom he married when he was 51 and she was 22. For years Trudeau, more like Mackenzie King than he’d care to admit, had lived with his widowed mother while dating innumerable women. He later admitted that Margaret was unique and had absolutely enchanted him at their first meeting: “I found her eyes extraordinarily beautiful.”

The Trudeaus would have three sons. The first, Justin Trudeau, now leader of the Liberal Party, was born on Christmas Day, the first child to be born to a sitting Prime Minister’s wife in over 100 years. But the Trudeaus’ fairytale marriage couldn’t last. Because of what she described much later as her bipolar condition, Margaret Trudeau’s behaviour became increasingly erratic and unpredictable. After many conflicts, including her famous night spent partying with the Rolling Stones in Toronto, they separated permanently.

And yet inevitably, with three sons in common, the Trudeaus’ relationship continued for many years on a different basis. It’s impossible to forget the heartrending photograph of Margaret and Pierre leaning on each other for support after the accidental death of their youngest son, Michel, in an avalanche in 1998.

Readers interested in more about love and sex in Canada’s capital can read Heather Robertson’s More Than a Rose: Prime Ministers, Wives and Other Women.

Laurier in Love Q & A

Laurier in Love covers just five years in Laurier’s romance with Émilie and his career in politics. Why did you want to confine the novel to those few years?

Roy: Those years 1896-1901 were full of dramatic events, beginning with Laurier's ascension to power, followed by the Queen's diamond jubilee celebrations, the South African War, the turn of a new century. Laurier's relationship with Emilie had already been going on for many years when the novel opens. I needed a tighter time frame to give focus and shape to the story. It could sprawl outside that frame a bit with flashbacks and flash forwards, but the main action had to be focused on dramatic events. Equally important, Laurier's entering Ottawa in triumph coincides with Zoe and Emilie arriving to live in the capital, so the final battle between them is joined.

There are two parallel stories in the novel, one relating the love triangle and the other involving Laurier's politics. The two stories constantly crisscross. Are the politics essential to understanding the triangle?

Roy: Yes, the two plot-lines are continually interwoven. I see Laurier as being in love not only with Zöe and Émilie but with Canada. He approaches all these relationships as a compromiser, a bridge builder, trying to be all things to all people. His approach works equally well or badly with the women and the country, until finally he's forced to take a stand. So yes, the politics are essential to understanding the triangle. The makeup of a leader's psyche determines how he does both relationships and politics – look at the current Prime Minister, Stephen Harper. In the novel I didn't want to sacrifice the politics to the love triangle. I wanted to portray Laurier in full, so that readers could understand how and why he shaped the country as he did.

Why was there never a public scandal over the relationship between Wilfrid and Émilie? Didn't his political opponents try to exploit the romance, or at least generate a whisper campaign against him?

Roy: Laurier's opponents did use gossip and a whispering campaign against him, especially in Quebec, during his early years in politics. But he ignored it, choosing not to fan the flames into a scandal, and eventually people got used to the triangle and accepted it as almost normal. Plenty of people saw the resemblance between Laurier and Armand and drew their own conclusions. Laurier was such an impressive man, with an impressive manner and intellect, that I think people, including the press, were afraid to attack him on personal grounds. Compare this with the similar press treatment of Trudeau, at least before Margaret's blatant indiscretions. Even today, rumours about Prime Ministerial marriages float around Ottawa, but the media are very wary of touching the subject. It's surprising, given that politicians' private lives are usually considered fair game, far more than in the 1890s.

There are repeated allusions in the novel to the closeness of King and Bert Harper. Do you think their relationship was more than Platonic?

Roy: It's easy to speculate but impossible to know. Today they'd probably be partners, but in their own time they were conventional, high-minded Victorians. They dated young women, and of course Willie visited female prostitutes, as we know from his diaries. But we can't know what he and Bert Harper got up to in their apartment. I have to believe there was at least love between them, certainly on Willie's part, since he dedicated himself to getting the Galahad statue erected on Wellington Street outside the Parliament Buildings in tribute to Harper’s heroism – and it's still there today. There's more evidence for erotic speculation about Laurier and Émilie because of their passionate love letters and the resemblance to Armand.

With thanks to Paul Gessell.